“Chapter one. He was as tough and romantic as the city he loved. Behind his black-rimmed glasses was the coiled sexual power of a jungle cat. I love this. New York was his town and it always would be.”

Manhattan is not just an ideal Woody Allen prelude to the stimulating imaginative architects known to cinema as dream movies. Despite its interior, charm, and wit, the film is filled with both nostalgia and time that reincarnates itself into a city that, despite its strong hold on reality and high existential crises, is the high hope of love and surprise for Allen’s own dream movie. As the film slips away from Allen’s flawed voice-over, past the lustrous black-and-white streets that encapsulate the “hustle-bustle of the crowds and the traffic”–beautiful women and street-smart guys–slowly entangled with the illusive orchestra notes from George Gershwin, the film swiftly speaks its seriousness on living life to its fullest. Not coming off too fabricated or perplex, Manhattan speaks through imagery and sound and shapes together, through its countless shots of New York City’s twinkling lights, entangled indulgence of love, couples briskly walking through the snow-splattered streets, and swarms of crowds meeting for the same amusement. The importance of connection, most importantly human connection, and the fragility, feelings and romance that follows.

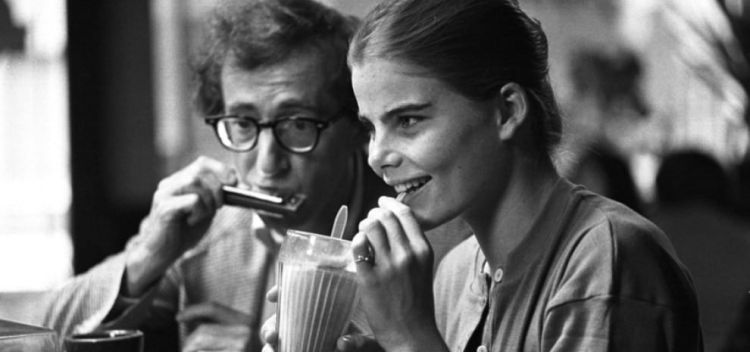

The first scene is laid out in ‘Elaine’s’ jazz-induced restaurant, where the audience are introduced to the man behind the rather comic and disorientated voice, Isaac, followed by his seventeen-year-old girlfriend Tracy (Mariel Hemingway) and two friends Yale (Michael Murphy) and Emily (Anne Byrne). Affirming that “talent is luck and courage,” the scene dives deep into the main themes of relationships and fondness, but proceeds to saturate the film in the essence of one’s first encountered attraction. Through drinks and a prompted question that makes the foursome contemplate their integrity, Isaac proceeds to light a cigarette in his mouth, causing Tracy to grasp a muddled expression and remind her forty-two-year-old boyfriend that he doesn’t smoke. Agreeing with her, Isaac responds to his girlfriend’s scoff by stating that he doesn’t inhale as it causes cancer, but chooses to plant the cylindrical roll of shredded, ground tobacco between his two lips because he looks “so incredibly handsome with a cigarette” that he cannot not smoke one.

The idea that Isaac acknowledges the pretense of doing something he knows he shouldn’t, but can’t help but carry on because it looks so good, ultimately showcases the intense eruption in humankind’s selflessness. How many people find it important to present themselves truthfully, despite how they appear to others? What number of the many that walk across Central Park, sinking in the surreal landscape of its warmth and sun, are going to rely on what looks good? The characters onscreen, like Isaac, are living in a city where presentation becomes more mature than integrity, eventually becoming the embodiment of the Broadway sign that flickers on and off between 42nd and 53rd Street–shadowing their revulsion of choices from their path of uncertainty. And maybe that’s what Allen was trying to put forward: the single making of a connection with another person, whether romantic or not, is always combined through elements that sometimes aren’t entirely true. That reality is, at best, immersed by one’s fixed dream.

Manhattan is a film that dedicates its lush Gershwin montage of the city and long conversational takes on adulterous affairs and life’s confessions, to the livelihood of New York City. A picture that captures not only the lack of cabs in the dense traffic, but an unemployed, frustrated television writer whose irony and perfect wit of human behavior collide perfectly with his charming diatribes on art and love. A lustrous piece of cinema that combines the modern, bittersweet humor, and timeless romanticism through finding and retrieving compassion. It’s a memoir that, even five decades on, remains as compelling as ever. To this day, performances from the glorious Meryl Streep and Diane Keaton come off as timelessly as the low-key gems that flowed from “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Manhattan is a love letter that is, understandably, a sincere and personal confession. A confession to humanity about how one can be so immersed in their own faithful pleasure and illusory that the sole energy and excitement within reality is painstakingly forgotten. The charming litany of escapism ultimately erupting emotional and artistic crises, in a place that was once remarked as pretty when the lights came up.